Jared Leto, Liberalism, and Coming of Age in the 2010s

The year is 2014. I’m 16 and my dream is to be a foreign correspondent for Vice Media. I romanticize the aesthetics of Occupy Wall Street and the Vietnam War protest movement, and my bedroom walls are plastered with photos snipped from a Time Magazine special on the Arab Spring. I procrastinate my math homework, instead pouring over features detailing strife in faraway places recounted by journalists who work at liberal legacy publications. Barack Obama has clinched his second term, and the Iraq War is a distant memory (Afghanistan, a question mark best ignored). I’m sitting in my parents’ Seattle living room watching the TV where Fred Armisen and Anna Kendrick are presenting the Independent Spirit Award for Best Supporting Male to Jared Leto for his performance as Rayon in Dallas Buyers Club.

Have I seen Dallas Buyers Club? Nope. But as Leto mounts the stage, beachy tresses bouncing, the red flannel tied about his waist flapping at his knees, I’ve discovered my new favorite actor.

When Air Mail released an exposé in June 2025 detailing the allegations made by various women accusing Jared Leto of sexual misconduct (many of the alleged episodes occurred when the women had been underage), I was saddened, but unsurprised. Rumors had been circulating for years, and by this point, I’d written Leto off as a self-absorbed has-been. But deep within, I couldn’t ignore the stab of shame: I had once idolized Leto.

It wasn’t his talent as an actor — I’d only seen clips of Leto in Dallas Buyers Club, and to this day, I doubt my ability to stomach the gangrene scenes from Requiem for a Dream — and his band, 30 Seconds to Mars, had never made it into my mixes. No, it was what Leto embodied, in conjunction with his Hays Code-era good looks, that had so endeared him to my 16-year-old self.

At the Independent Spirit Awards, Leto was pure 2010s swagger. With a trophy in hand, he thanked Mark Twain, David Bowie, Pink Floyd, Ansel Adams, Jackson Pollack, Steve Jobs, Mozart, C.S. Lewis, River Phoenix, Kurt Cobain, and the “seven billion people on the planet.” He made self-deprecating, expletive-laced jokes, and the crowd cheered. He thanked “All the women I’ve ever been with and all the women who think they’ve been with me . . .”

Leto was cool. He didn’t fall in line and cut his hair like all the other Hollywood stars. He was irreverent, saying “fucking” and talking about sex. His fashion exuded an internationalism (the flannel evocative of a kilt, the gauzy black and white scarf around his neck almost a keffiyeh) firmly rooted in Levi’s-coded Americana. He referenced great writers and starved himself in the name of art. The man was so in touch with his masculinity that he would play a trans woman — how radical, how accepting.

A week later, I watched Leto retake the stage, this time to receive an Oscar. He’d classed it up a bit with a white blazer and burgundy bow tie. The sex jokes and expletives were replaced with a heartfelt nod to his single mother (who was also his date), followed by a shoutout to “all the dreamers out there around the world watching this tonight in places like the Ukraine and Venezuela.”

…

In a 2018 essay “Liberalism in Theory and Practice,” Luke Savage writes of being “trained by mainstream political culture to think of liberalism as an orientation synonymous with change, progress, even dissent.” To me, a teen coming of age in the 2010s, Jared Leto was the embodiment of liberalism. He struck me as a progression of the Hollywood leading man — bearded, vegetarian, and carrying the baggage of a working-class childhood. By pledging his support for the LGBTQ community and promoting foreign struggles against “authoritarianism,” Leto aligned himself with the underdogs, the forgotten, and the systemically exploited.

That Leto’s whiteness, cis-ness, thinness, and class status were perfectly aligned with hegemonic standards — well, that didn’t occur to me. Neither did the fact that, among the myriad mass political movements of the time, he chose to highlight two that happened to be pro-Western.

It was the early 2010s, baby — analysis of inconsistencies between rhetoric and reality was just so gauche. America had emerged from the dark shadow of the Bush administration, from Abu Ghraib and the Great Recession; embarrassments such as the whole “weapons of mass destruction” kerfuffle were things of the past. Obama was president: change was on the horizon, and goddamn did I believe in it.

The dream of American liberalism in the 2010s was defined by what it was not — we weren’t going to let the bad apples of the Bush administration spoil the barrel of American exceptionalism. Look at Leto’s own background — only in America could a single teen mother “crawl out of the muddy banks of the Mississippi with [two children] in one hand and a fistful of food stamps in the other” (his words) and go on to raise an Oscar winner. We were the nation of rag-tag dreamers, a sea of Alexander Hamiltons as played by Lin-Manuel Miranda.

It’s hard to pinpoint my own path from liberalism to the undefined democratic socialist mess I identify as today, but it maps pretty well onto the timeline of my disenchantment with Jared Leto. By 2015, cracks were showing. Whispers of drone strikes curdled the edges of American international policy, and we’ve been in Afghanistan for an awful long time now, haven’t we?

With the arrival of 2016, I looked forward to what I was confident would be a historic achievement. We reclined in assurance, knowing the extensively qualified candidate who was to take on the esteemed role would deliver a performance rivalling even the smashing success we’d witnessed in 2008. Despite occasional hiccups, moments of public embarrassment, and rumors of conflict below the surface, the powers that be soothed our hesitations, urging us to trust the system — how wrong they were.

I’m of course referring to Jared Leto’s performance as the Joker in Suicide Squad.

2016 was a year of failure for both Leto (most of his scenes from Suicide Squad were cut, and what remained was shredded by critics) and the liberal establishment, à la Hillary Clinton’s devastating loss to Donald Trump. It signalled an erosion of trust in elites, both cinematic and political, and left me, a college freshman, with an icky feeling toward both Leto (had he really sent Margot Robbie a rat? Opened condoms too? Kinda poor taste) and liberalism (why did they have to do Bernie like that?).

Despite my mounting distrust in the liberal establishment, I continued to register as a Democrat, figuring a party that mostly recognized climate change and offered tacit support for equality (despite a seeming refusal to address the root causes of these issues) was better than the Trumpian alternative.

I bit my tongue in 2019 when photos from 30 Seconds to Mars’s “Mars Retreat” featuring Leto in full Jesus-face standing before his “Echelon” of young women, all dressed in white, were released. The optics didn’t seem great, but then, as the band’s much-used hashtag #YouWouldntUnderstand professed, maybe it was just me (because I sure as hell didn’t understand).

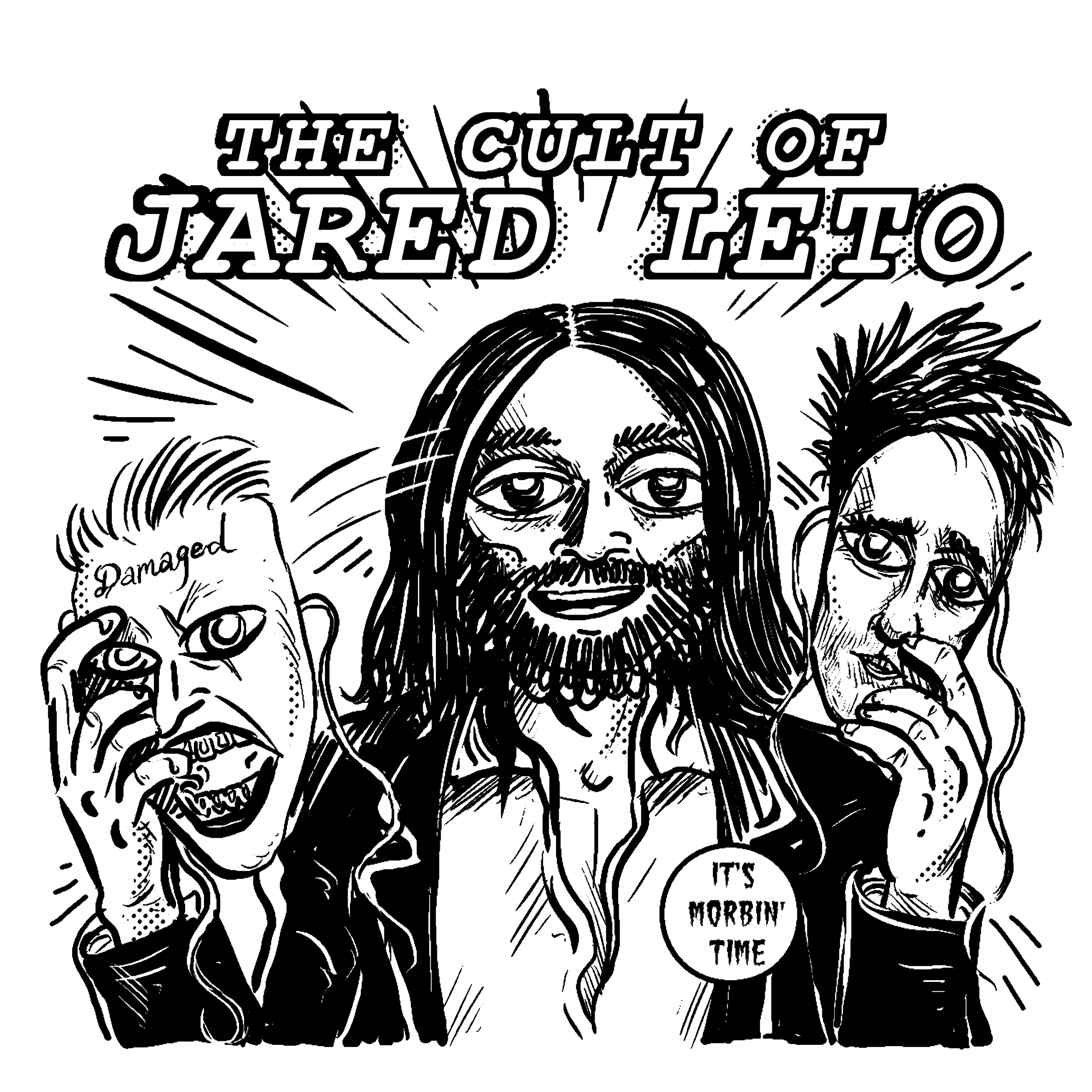

Sketch by Romey Petite

By 2022, I’d lost most of my faith in the liberal dream. Biden was president and the kids were still in cages and headlines of racist police violence were no less frequent, and though the Afghan War was technically over, U.S. drones were still accidentally murdering civilian families in the country—and like a ray of light from the darkness, Morbius made its triumphant theatrical release, then it was pulled, then it was released again because Sony failed to understand internet irony.

Unlike many of Leto’s films, I’ve actually watched Morbius. It’s bad. It’s not “fun bad,” as Leto tried to brand it. The plot is borderline incoherent, and Leto’s acting is stiff; the script reads like it was written by an AI. How did the great method actor and radical artist Jared Leto sign off on something like this? He must have changed; perhaps fame had corrupted him.

The meme of Morbius led me down a Jared Leto rabbit hole. I re-watched that Independent Spirit Award speech that had so endeared me to Leto as a teenager. It’s not just that it’s aged poorly, what with Leto’s sly gaslighting and the fact that a cis man is being celebrated for taking one of the few roles available to trans women actresses, the speech is just cringey. Leto comes off as self-involved and vacuous.

The research continued. I read articles detailing Leto’s long-term friendship with Terry Richardson, a fashion photographer who has faced numerous and very public allegations of sexual misconduct (it was even alleged that, before opting to take his mother, Leto had intended to bring Richardson as his Oscar date). I read that in 2018, actor Dylan Sprouse had tweeted about Leto “slid[ing] into the DMs of every female model aged 18-25” and that director James Gunn had replied “He starts at 18 on the Internet?”

A new portrait of Leto was forming, one of a powerful man with a history of inaccurately representing his past, who, at the very least, has had some concerning interactions with much younger women.

After reading an unhinged interview directly following Leto’s Oscar win in which he discussed how his Oscar acceptance speech may impact 30 Seconds to Mars’ impending performance in Russia, “I read that they censored my speech in Russia. They cut what I said about Ukraine. But I’m fully intending to sing ‘This is War’ there . . . Shit could go down,” I decided it was finally time.

I’d listen to 30 Seconds to Mars.

Curious to see what kind of rabble Leto had threatened to rouse in Russia, I clicked on 30 Seconds to Mars’ 2009 music video for the eponymous single from their third studio album, This is War.

The video opens with that classic H.G. Wells quote about how “If we don’t end war, war will end us,” followed by the simple preamble: “This is a song about peace.” I was having flashbacks to We Day events and the Kony 2012 documentary already.

In what I can only describe as a “pentagon-esque” series of clicks, the screen flashes to a map of the world, zooming in on West Asia before snapping again to a shot of desert mountains, washed out as if to evoke the aesthetics of American shoot-and-cry epics like The Hurt Locker and Black Hawk Down. Here we find Leto’s band, dressed as marines and cruising down a dirt road in a Humvee. The landscape looks suspiciously like inland California.

The song itself is something akin to new wave with echoes of Emo, which is to say, the most generic 2010s-era pop-rock you’ve ever heard. Leto’s perfectly adequate vocals rhyme “people” with “evil,” “civilian” with “victim.” Interspliced with the footage are historical clips from war zones, sometimes with lyrics from the song superimposed over top. Someone in the band fires a flamethrower at one point. Mostly, “This is War” seems to serve as a vessel through which Leto can scream-sing “To the right, to the left / We will fight to the death” while discharging various guns in slow motion. His eyes are incredibly blue.

This is Leto’s great anti-war anthem: a collection of clichéd platitudes set to pop rock.

I don’t know what Jared Leto as a person is like (though if the allegations against him are even half true, they cast a pretty unappealing portrait), but Jared Leto the figure is perfectly encapsulated by “This is War.” He ensconces himself in the aesthetics of radicalism, speaks the persona of a tortured artist into existence, and then makes a (very expensive) little music video that’s about as subversive as the Pledge of Allegiance.

Jared Leto upholds the bastion of liberal ideology that tells us superimposing the word “liar” over footage of Richard Nixon and “evil” over George Bush (yes, these things both happen during the video for “This is War”) is a bold political statement. This is the same ideology that encourages Democratic senators to call for the humane treatment of undocumented migrants, then support a bill that would have delegated billions to ICE to expand its immigration detention facilities. It’s Obama pledging change, then bailing out the banks that caused the 2008 financial crisis.

My admiration for Jared Leto was fed on empty aesthetics and internalized biases. I didn’t care about his acting or his music. I liked him because I liked pretty white men who were privileged enough to be crass and alt and strange and still get jobs.

My alignment with American liberalism was no different. I never really checked to see if Obama, Clinton, and Nancy Pelosi’s policies were actually resulting in concrete improvements, not just in my life but in the lives of everyone else. I’d internalized American exceptionalism and trusted that our country was ultimately a vessel of good, that our best and the brightest would bring about better lives for all, that this was the nation’s purpose.

…

The year is 2025. Trump has been elected for a second term as president. My tax dollars are enabling a genocide that’s killed an estimated 65,000+ people. The country appears to be sliding deeper into far-right authoritarianism as the best and brightest liberal politicians who I keep voting for twiddle their thumbs. The American liberal belief that capitalism and imperialism just needed some gentle tweaking to achieve democracy and equality—well, that’s fully shattered. Should’ve seen it coming.

The year is 2025, and Jared Leto has allegedly been taking advantage of underage girls for decades. Should’ve seen that too.

It’s a terrifying world, and sometimes I miss the optimism of the 2010s, when single-word slogans promised radical improvements and a 42-year-old guy in a kilt and winter hat was just a silly, charming artist. But maybe this is the time for real optimism. Maybe we’ll actually listen to the women hurt by Leto. Maybe we’ll address the injustice inherent to the American project.

Or maybe we’ll forget it all in the chaos and terror of today, and instead seek refuge at the 30 Seconds To Mars benefit concert for the Booker/Cheney 2028 campaign.