Jesse Welles and the Resurrection of Artistic Confidence

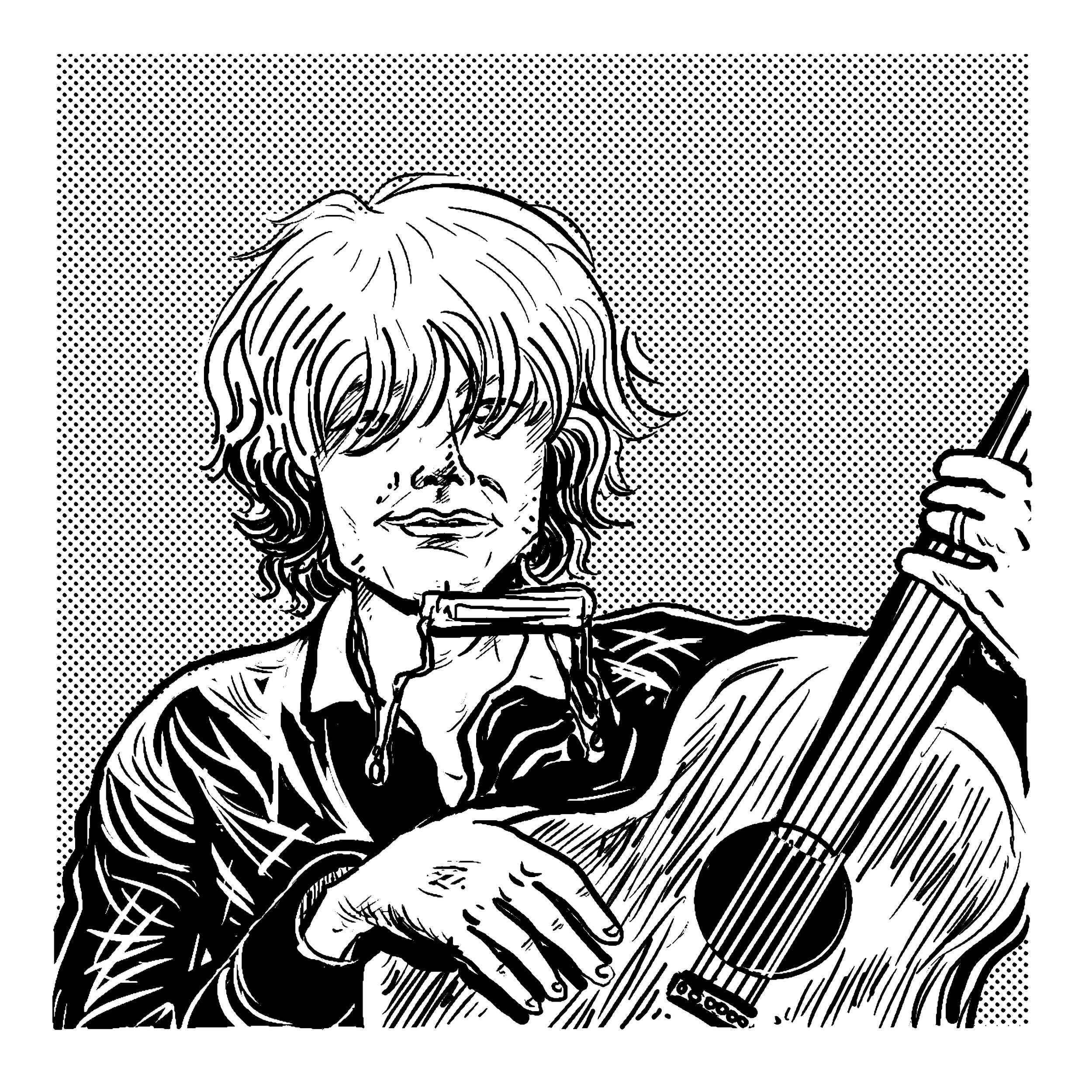

Image Source: Spartan, Sacha Lecca for Rolling Stone, Jesse Welles warming up in the green room at Bowery Ballroom.

“If we can preserve the memory of days and of faces, and if, conversely, faced with the world’s beauty, we manage not to forget the humiliated, then Western art will gradually recover its strength and its sovereignty.”

~ Albert Camus

I’ve often thought that I was born in the wrong generation.

Take a look at my bookshelf, my Spotify playlists, and my recently watched—you’ll find a majority of art made long before my time. But I’m far from original in this sentiment. Which raises the question, why are so many of us attracted to the art of older generations? What has changed in modern creation that leaves us feeling unfulfilled?

The good news is, I’ve found a clue. He’s scruffy-haired, 5’7”, dresses in the clothes my grandfather used to wear, and seems to forever breathe through a harmonica. His name is Jesse Welles, a 32-year-old folk-singer, songwriter, and poet whose backwater presentation is rooted in his working-class, Ozark, Arkansas upbringing. He has been hailed by many as the Bob Dylan of the new generation. I believe he’s the reincarnation.

Welles’s music is considered by many to be edgy. One popular piece, “War Isn’t Murder,” is structured as a series of snide remarks towards political leaders and super moguls. As he puts it, “War isn’t murder/ that’s what they say/ when you’re fighting the devil/ murder’s okay.” Another title, “The Poor,” sings the woes of growing up working class in a financial system that is set up to protect the status quo. According to Welles, he “must’ve missed the part/ where they taught the art/ of private equity.”

It’s likely at first to be put off by these frank truths. In fact, Welles’s recent social media growth is due in large part to his unbearable acknowledgement of reality. These are problems that —when we have the privilege— we tune out. In 2024, Welles’s protest songs sprang to YouTube algorithm relevancy because of this backlash, which has since launched his career to new heights.

But what I find most fascinating about Welles is not what he’s saying but rather his explosion into relevancy despite him saying it. It took me finding him to realize what it was that drew me to those old artists, why I felt disconnected from the mainstream art being produced today. Welles doesn’t bend the knee.

* * *

In Bristol, 1997, a mural appeared overnight of a teddy bear hurling a Molotov cocktail at a group of riot police. The piece was tactically placed over an advertisement for a lawyer’s office. Although the piece itself wasn’t all out of place in Stokes Croft, a neighborhood known for its larger-than-life cultural scene, it would live on as the first guerrilla work from one of the greats: Banksy.

The Mild Mild West. Photographer: William Avery. Date taken: 5 April 2007.

Since that piece, The Mild Mild West, Banksy has gone on to produce graffiti, paintings, films, and more. His work is wholly anti-establishment, and he remarkably always seems to be ahead with his commentary on the next political discourse.

Albert Camus, in his 1957 essay, “Create Dangerously,” argues that art’s value comes from its response to political injustices. That if a piece of art doesn’t require some courage in its creation, then it’s a failure to those who cannot speak up for themselves. Banksy’s work is the epitome of this postulate. In 2003, he painted “Love is in the Air,” a commentary on Israel’s territorial exclusion in the West Bank. In 2019, he created “Migrant Child,” a mural in the Venice canals highlighting the ongoing migrant crisis. This past week, he painted a mural of a judge—adorned with a traditional white wig—beating a protester, created just days after mass arrests at a pro-Palestine rally in London. Banksy creates dangerously.

When I launch Spotify today, the advertised artists include Sabrina Carpenter, Benson Boone, and Morgan Wallen. While it’s true that these artists are no strangers to controversy—Carpenter’s recent album cover, Man’s Best Friend,was disparaged for its overt sexuality—the type of music they create falls far short of Camus’ credence. Modern artists, by and large, create works for the masses. In an era of globalized reach, quantity is the name of the game. Record labels are still the domineering player in music consumption, and with Spotify swindling artists at every turn, appeasing them is a necessity for musicians looking to build their career. Controversial creation is a risk that few are willing to take.

Just look at the Billboard Top 100 songs from the 2020s. By and large, these songs are stylized, square-peg products that strive for mass relatability. They are antithetical to Camus’s role of the artist. And while art’s value should not be solely derived from its controversiality or its ‘deeper meaning,’ I think they certainly play a big role. There was no risk in Shaboozey writing “A Bar Song (Tipsy),” which sat at the top charts for 19 weeks and earned him $10 million.

It was here that I realized why I was so uncomfortable with modern pop culture art. It’s not nostalgia, it’s not the skill of the artists, it’s not even the type of work being produced. Instead, it’s that so many artists are creating for the money or status, rather than for the art of creation itself. We have essentially destroyed art for art’s sake by optimizing our work for the audience, by ensuring that we don’t offend, that we don’t anger, that we allow people to feel comfortable.

But comfort may be the farthest thing from Banksy’s mind. His work, like the work of Welles, pushes us to take a deeper look at the world around us, at the things we take for granted. We need art to be uncomfortable; we need art to inspire conversations amongst us. We need art to shine a torch into the damp cell of society in order to notice the shine of the key.

Sketch by Romey Petite

The trick is, of course, we don’t know who Banksy is. There is speculation, sure, and his unknown identity certainly adds to his allure, but throughout his career, he’s had the fortune of running commentary through public connections and news groups. He hasn’t had a video interview since 2003.

When I first thought to compare the artistic rebellion of Jesse Welles with that of Banksy, I couldn’t quite connect the dots. It’s true that much of their work comments on similar injustices, but that’s about where the similarities end. I realized what appeals to me about Welles is that he’s unabashedly confident in his message. He’s the downtrodden David, forwardly facing off against Goliath.

So how then can we encourage artists to take risks when big business funnels money towards conformity?

The answer is in Jesse Welles’s story—by utilizing social media. During his early music career, Welles posted regularly on SoundCloud and Bandcamp with lackluster results. It wasn’t until he turned his attention to platforms like YouTube and TikTok in recent years that his music began to leak into the mainstream. Some of his most viral videos have garnered over 2 million views on YouTube, and his most popular song, “War Isn’t Murder,” has over 6.5 million streams on Spotify. As Banksy put it, “This is the first time the essentially bourgeois world of art has belonged to the people.”

Social media algorithms are programmed for virality, often not discriminating between content that people react positively to with content they don’t. For artists like Welles, this allows his work to grow: reaching more people, even with a negative comment or angry share. Throughout this growth, if his work’s messaging can reach just one person, if it can make them stop and reconsider, if it can make them think about Camus’s unheard voices, those who are unable to stand up for themselves, then it will have been worth it.